During this holiday season, the usual holiday TV shows, movies, and conversations abound. An interesting one surfaced yesterday. “What do I tell my young daughter about Santa Claus? I’d like her to experience the joy that comes from believing, but I know she’ll hear from at least one of her friends that Santa isn’t real. And what do I say if she asks how there can be so many Santa’s available at the same time? Shouldn’t Santa still be at the North Pole?”

Tough one. Should we be positive or negative? Whimsical or realistic? Literal or figurative? How is a parent to choose?

Organizations face the same struggles in the stories they tell – to themselves, their customers, their stockholders, and the increasingly connected world. Is it more fair/ethical/ helpful to tell only the cold, hard, unvarnished “truth” of quality problems, declining morale, and poor prospects? Or do we exclusively focus on the uplifting story– new products in the pipeline, aggressive business development efforts, successes of high performing teams and continuous improvement training initiatives? Perhaps a mix would be best – but how much of each?

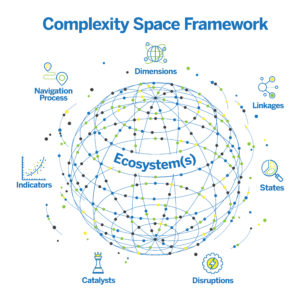

Stories are one of seven Catalysts in the Complexity Space™ Framework (CSF). In the CSF, Catalysts are the short-term, intentional actions we can take to influence organizational patterns of thought and behavior. Think of them as chess pieces we need to move to keep the game going. We move them intentionally, with a strategy in mind, recognizing there are no guarantees we will accomplish our ultimate outcome.

Which stories does your organization tell? How many? Who tells them? How consistent are they? How frequently are they told? Who listens to them? Each of these questions invites both an invitation to engage in a conversation and try an experiment – What happens when you change the answer to one or more of those questions?

When conducting an experiment or moving a chess piece, the goal is to consider your strategy carefully before actually making the move. What might be the impact – intended and unintended — on other elements of the CSF?

To end this post where it began, “What do I tell my young daughter about Santa Claus?”

(With credit to the TV show Family Feud …)

Audience answer #3: “Yes, darling, Santa is real. He is at the North Pole now. These others are Santa’s helpers, collecting lists and spreading joy.”

Audience answer #2: “Santa is a symbol that represents happiness, joy, and giving. All these Santa’s you see are here to remind us of those things.”

Audience answer #1 (drum roll, please …): “Ask your [other parent or caregiver)!”

A colleague recently shared that his aerospace engineering and manufacturing facility had just announced a major layoff at. We had worked there together in the past, so I was familiar with the facility and organizational ecosystems.

A colleague recently shared that his aerospace engineering and manufacturing facility had just announced a major layoff at. We had worked there together in the past, so I was familiar with the facility and organizational ecosystems. Each Ecosystem holds enduring, pervasive, and hard to influence Dimensions

Each Ecosystem holds enduring, pervasive, and hard to influence Dimensions Access modeled a willingness to take a risk across the entire company as demonstrated in their four “steps” to improving corporate culture (shown in the graphic). Each step is a clear commitment to total engagement with each and every employee – from asking tough questions to receiving tough feedback through the resulting actions taken to make a change (or shift a pattern).

Access modeled a willingness to take a risk across the entire company as demonstrated in their four “steps” to improving corporate culture (shown in the graphic). Each step is a clear commitment to total engagement with each and every employee – from asking tough questions to receiving tough feedback through the resulting actions taken to make a change (or shift a pattern). How can anyone not be struck by the unique challenges and opportunities that have been ushered in with the new year? Those challenges include aligning the needs of employees, the environment, shareholders and customers; establishing a new level of security across our physical and digital spaces; addressing challenges from inside as well as outside of an organization that we cannot control; and influencing shifting tensions in a healthy and healing way.

How can anyone not be struck by the unique challenges and opportunities that have been ushered in with the new year? Those challenges include aligning the needs of employees, the environment, shareholders and customers; establishing a new level of security across our physical and digital spaces; addressing challenges from inside as well as outside of an organization that we cannot control; and influencing shifting tensions in a healthy and healing way.